Researchers grow 'mini-eyes' to understand genetic disease

5 Jan 2023, 2:40 p.m.

In a world first, researchers at UCL Great Ormond Street Institute of Child Health have grown ‘mini-eyes' to better understand the development of blindness in a rare genetic disease called Usher syndrome.

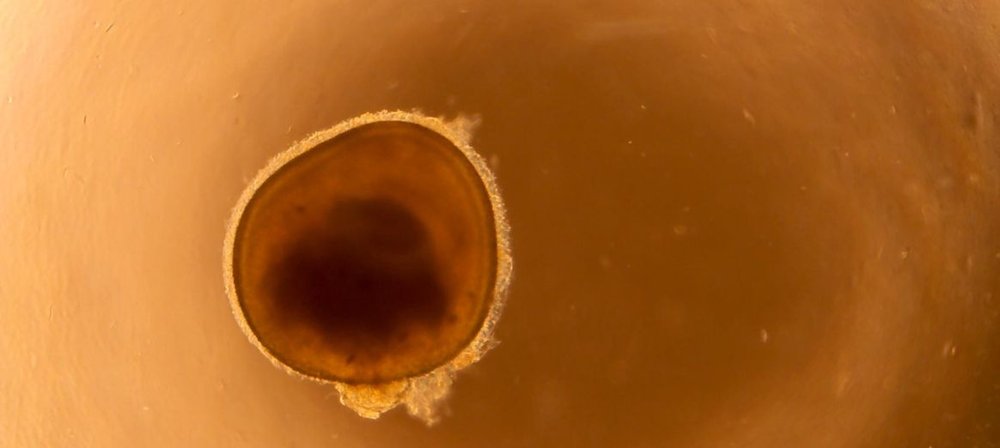

The 3D ‘mini eyes’, known as organoids, were grown from stem cells generated from skin samples donated by patients at GOSH.

In a healthy eye, rod cells - the cells which detect light - are arranged in the back of the eye in an important region responsible for processing images called the retina. In this research, the team found that they could get rod cells to organise themselves into layers that mimic their organisation in the retina. This produced a ‘mini eye’.

A paper outlining this research has been published in Stem Cell Reports. The senior author of the paper is Professor Jane Sowden.

Over the past decade, GOSH Charity has supported Professor Sowden's various research projects. This has been in collaboration with other groups, including Life Arc, and more recently through the National Call. Early seed funding on retinal stem cell therapy and research on root causes for poor vision that spans her work has contributed to this exciting breakthrough.

An important step forward in understanding sight loss in Usher syndrome

Previous research using animal cells couldn’t mimic the same sort of sight loss as that seen in Usher syndrome. So, these ‘mini eyes’ are an important step forward.

Usher syndrome is the most common genetic cause of combined deafness and blindness. It affects approximately three to ten in 100,000 people worldwide. Children with Type 1 Usher syndrome are often born profoundly deaf. Their sight slowly deteriorates until they are blind by adulthood.

Cochlear implants can help with hearing loss. There are currently no treatments for retinitis pigmentosa, which causes vision loss in Usher syndrome.

While this research is in early stages, these steps towards understanding the condition and how to design a future treatment could give hope to those who are due to lose their sight.

Analysis more detailed than ever before thanks to organoids

The ‘mini-eyes’ allow scientists to study light-sensing cells from the human eye at an individual level and in more detail than ever before.

Using powerful single cell RNA-sequencing, it is the first-time researchers have been able to view the tiny molecular changes in rod cells before they die.

Using the ‘mini eyes’, the team discovered that Müller cells, responsible for metabolic and structural support of the retina, are also involved in Usher syndrome. They found that cells from people with Usher syndrome have genes which are abnormally turned on for stress responses and protein breakdown. Reversing these could be the key to preventing how the disease progresses and worsens.

As the ‘mini eyes’ are grown from cells donated by patients with and without the genetic ‘fault’ that causes Usher syndrome, the team can compare healthy cells and those that will lead to blindness.

Understanding these differences could provide clues to changes that happen in the eye before a child’s vision begins to deteriorate. In turn, this could provide clues to the best targets for early treatment - crucial to providing the best outcome.

Hope for future treatment – Professor Sowden

“We are very grateful to patients and families who donate these samples to research so that, together, we can further our understanding of genetic eye conditions, like Usher syndrome,” Professor Jane Sowden says of the research.

“Although a while off, we hope that these models can help us to one day develop treatments that could save the sight of children and young people with Usher syndrome."

Reusing the ‘mini eye’ model to study other diseases

The ‘mini eye’ model for eye diseases could also help teams understand other inherited conditions in which there is the death of rod cells in the eye, such as forms of retinitis pigmentosa without deafness. Additionally, the technology used to grow faithful models of disease from human skin cells can be used for a number of other diseases - this is an area of expertise at the Zayed Centre for Research into Rare Disease in Children.

Future research will create ‘mini eyes’ from more patient samples, and use them to identify treatments, for example by testing different drugs. In the future, it may be possible to edit a patient’s DNA in specific cells in their eyes to avoid blindness.

This research was funded by National Institute of Health Research Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre, Medical Research Council, GOSH Charity and Newlife the Charity for Disabled Children.